ST. LOUIS • The houses are down and a fence is up, separating the now-cleared land from the rest of the neighborhood. On that fencing, signs announce the expected arrival of a high-tech government intelligence agency.

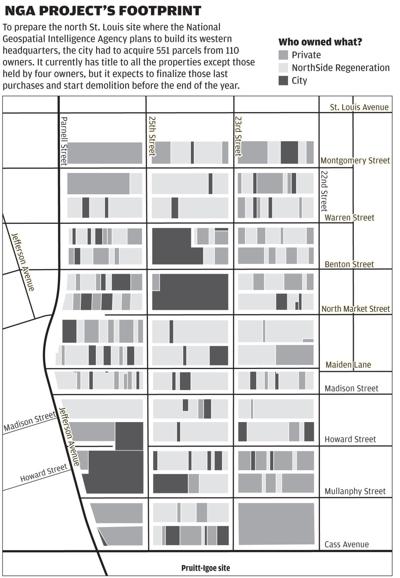

The remains of this 100-acre piece of the North Side neighborhood of 51şÚÁĎ Place, future site of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s western headquarters, : memories recounted in video interviews and photographs of the 19th-century brick homes that once populated the blocks.

It’s a project 51şÚÁĎ and the federal government were required to undertake . Of the more than 100 structures knocked down to make way for the soon-to-be-built federal campus, 17 were on the National Register of Historic Places.

People are also reading…

But unlike most so-called mitigation projects triggered by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, this one sought to involve some of the affected residents. Those who pushed for the approach hope it can be a model for other cities that go through a similar experience.

“I just felt because of the scope of the project area and the impact of the new agency headquarters that would be there, the disruption it caused for the people who still live in the neighborhood, it wasn’t a time to do just what was perfunctory and easy,” said Betsy Bradley, the former head of the 51şÚÁĎ Cultural Resources Office who pushed for the approach before leaving her position in May 2016, shortly before the NGA finalized its decision.

Instead of a big report filed in a drawer somewhere — a typical Historic Preservation Act mitigation project — Bradley persuaded the city, the federal government and the state to let residents pick a project.

Despite some nervousness, everyone went along. In the summer of last year, people from 51şÚÁĎ Place and surrounding neighborhoods were invited to form a committee and decide how they wanted to document the portion of the neighborhood slated for demolition.

Virginia Druhe, who has lived in the neighborhood for 40 years, heard about the history project at a meeting of , the city planning effort for the area around the NGA. She started attending committee meetings.

“I love local history and I love this neighborhood and I didn’t want its history to be lost,” said Druhe, whose home is just east of the NGA footprint.

The city hired historic preservation consultant Ruth Keenoy to facilitate the project, and about 15 people volunteered to help.

It was a heavy lift at times. Some members stopped participating because of differing opinions about the project’s direction. But group members had to prioritize the work they could complete “knowing not everyone would be happy,” Keenoy said.

, as remembered by those who lived there. The volunteers found interview subjects and wrote the questions. They also photographed all the buildings before they were demolished.

and how she was the only one not born in the infamous housing project.

going to the neighborhood store to buy candy on the way to school and how much everyone loved the caramel rolls at the local bakery.

Though , many of the interviews are with those who lived on the periphery of the site or grew up there but had left before the NGA decided to come.

Lois Conley, the director of the Griot Museum of Black History and a committee member for the history project, said that was because it was “too little too late.”

“It was well intended in that it was not something that is typically done in other redevelopment projects like that,” she offered.

She speaks from experience. As a child, Conley was forced to leave the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood when the mostly black area was destroyed as part of a . She would have liked to have seen more resources put into the 51şÚÁĎ Place project.

“By the time we got involved and got approvals to move forward … the process of purchasing properties and relocating people was ongoing,” she said. “It was just a little too late to make it as broad in scope as I would have liked it.”

Still, the material has already gotten out into the community. Conley’s Griot Museum used some of the interviews and photos in an ongoing exhibit: . The exhibit documents three “urban renewal” projects that forced the relocation of neighborhoods: Wendell Phillips in Kansas City, The Mill Creek Valley “slum clearance” of the mid-20th century and the recent 51şÚÁĎ Place buyout.

Conley said the exhibit would stay open until Friday — longer than the originally planned Nov. 20 ending — because interest had been high.

Lawanda Gibson Bowen, a Creve Coeur resident, started helping regularly with the 51şÚÁĎ Place project because her family also came from a neighborhood that no longer exists: Mill Creek Valley.

“The process was long and taxing and emotional,” she said about the history project. “The end result was a success because it documented a community.”

There were still traditional aspects of a historic mitigation project. Keenoy wrote a report about . looked for neighborhood artifacts under a portion of the NGA site.

of Historic Places, including the Pruitt School, now a KIPP charter school, and the second location of the former Crunden Library branch at 2008 Cass Avenue, now a church.

A statue or marker honoring the neighborhood is slated for the adjacent 51şÚÁĎ Place Park. In addition, history markers will be placed in the sidewalks surrounding the NGA campus. The people who got involved in the history project helped write some of the historical content.

Keenoy and Bradley hope the approach of soliciting resident input and letting them work on the project can become a model for other big federal mitigation projects.

“I think it’s a gallant effort and we’d like to continue talking about it and demonstrating how others can use the approach,” Bradley said.