NEW YORK ŌĆö In one sentence, Marc Levin outlined the case for criminal justice reform in America.

ŌĆ£Justice for only those who can afford it is really not justice at all,ŌĆØ he said.

Levin is vice president of criminal justice for the , a conservative think tank based in Austin that has become one of the leading voices for reforming the criminal justice system.

He was speaking at a forum at focused on the concept of ŌĆ£cash register justice,ŌĆØ which unfortunately manifests itself in city and county courts all over the country, like those in Missouri that have been charging poor people for their incarceration and then putting them back in jail if they canŌĆÖt pay.

People are also reading…

When people of little means are treated differently in the courts than people with deep pockets, Levin said, those living in poverty are deprived of their liberty.

On the day Levin was speaking, about 1,000 miles to the west his organization was filing an amicus brief in a 51║┌┴Ž case that seeks to end the insidious practice of setting bail without taking the time to determine a defendantŌĆÖs ability to pay.

ŌĆ£A system that deprives individuals of liberty without a meaningful hearing and without regard to their personal circumstances is the very definition of a due process violation. The State may not jail a person solely because he has been arrested, and it may not jail him solely because he is poor. That he is both poor and arrested does not enhance the StateŌĆÖs claim on his liberty,ŌĆØ the foundation wrote in its brief. ŌĆ£Worse, the upshot of this regime is that punishment ŌĆö indeed, often the only jail time that will be inflicted ŌĆö occurs before trial and conviction, perverting the presumption of innocence that underlies our justice system. And this punishment often includes extreme temperatures, vermin infestations, and violence, all without a guilty plea or jury verdict.ŌĆØ

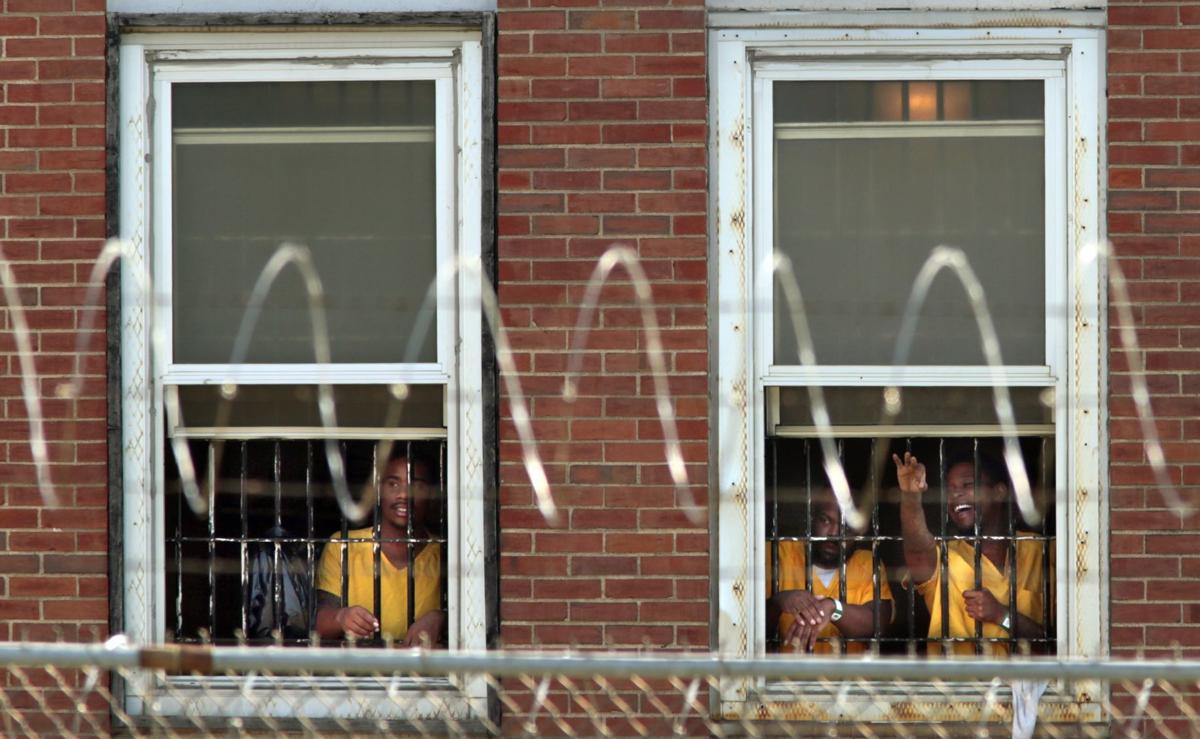

The brief was filed to support a lawsuit filed earlier this year by ArchCity Defenders and the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, seeking to declare the application of the cityŌĆÖs cash bail system unconstitutional. Traditionally, judges in 51║┌┴Ž were setting bail without regard to a personŌĆÖs circumstances, specifically the ability to pay. The result, of course, was a filling of the cityŌĆÖs medium security jail, known as the Workhouse, with hundreds of pretrial detainees, some of them on misdemeanors, some facing charges for violence, but nearly none convicted of the crimes of which they were accused.

U.S. District Judge Audrey Fleissig had issued an injunction forcing the city to adjust its bail procedures, but that injunction is on hold while the city appeals her ruling to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals, where the Texas Public Policy Foundation filed its brief.

At the time Fleissig issued her original injunction, attorneys for the cityŌĆÖs judges said that enforcing it would create chaos in the courts, requiring hundreds of hearings in a short amount of time.

Back in New York, a prosecutor from Florida, TampaŌĆÖs Andrew Warren, said thatŌĆÖs the reality all over the country.

ŌĆ£The bail system doesnŌĆÖt actually follow the law,ŌĆØ Warren said at the Cash Register Justice forum. ŌĆ£We detain people for inability to pay hundreds of times a day. ItŌĆÖs done that way because itŌĆÖs a fast-food industry.ŌĆØ

That industry, ignoring constitutional protections in a rush toward mass incarceration, is under attack from many fronts, with most of the attacks focusing on the dichotomy the system creates between those with money and those without.

But itŌĆÖs about more than that.

When a city like 51║┌┴Ž uses bail as a pretrial punishment tool, the foundation wrote in its brief, it actually makes the community less safe. This is the underlying argument behind the Close the Workhouse movement as well.

ŌĆ£51║┌┴ŽŌĆÖs bail system makes the community weaker by depriving citizens of community ties and the means to support themselves and by increasing the likelihood of future criminal activity,ŌĆØ the foundationŌĆÖs brief says.

To support its argument, the foundation refers to that looked at the likelihood of recidivism by people charged with crimes who were held in jail on high bail before trial, compared to those released and allowed to fight their charges while back in the community.

It was the pretrial defendants held in jail who were more likely to commit future crimes.

ŌĆ£Low-risk defendants held for two to three days were 40 percent more likely to commit new crimes before trial than those held for no more than 24 hours,ŌĆØ the brief says. ŌĆ£And low-risk defendants detained for 31 days or more were 74 percent more likely to commit new crimes before trial.ŌĆØ

Bail isnŌĆÖt supposed to be used to punish people accused of crimes, both Levin and Warren said this week. But in 51║┌┴Ž, thatŌĆÖs what the practice has been.

Some ŌĆ£tough-on-crimeŌĆØ types believe locking up those accused of crimes before theyŌĆÖve been convicted makes them safer. The reality, say the right-on-crime folks, is different.

51║┌┴Ž is less safe when it locks up poor people just because theyŌĆÖre poor.